Bird Migrations

- Feb 3, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 18, 2025

There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides, the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature - the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after the winter.

~ Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring

January 1st seems like a strange time to mark the start of a new year — it is neither an equinox nor a solstice. It does not herald a change in seasons, nor does it represent any natural or geographical event. Since 45 BC, it's a repeated refrain in human history, arbitrarily marked as we flip the (Gregorian) calendar pages to measure our earthly existence.

In the realm of nature, creatures keep their own clocks and calendars. Animals that embark on annual migrations are tuned to the lengths of days and seasonal cycles. Aquatic creatures synchronize their lives with the ebb and flow of tides, while nocturnal beings chart their course by the gentle glow of lunar clocks. Circadian rhythms, attuned to Earth's rotation, guide countless organisms through their daily routines. Those that need to travel under the cover of darkness, possess a sidereal clock that measures the apparent motion of a star around the Earth and acts as a cosmic guide.

Natural rhythms helped calibrate the clocks of different organisms; yet in a poetic twist, we now, look to these creatures as harbingers of seasons and change. For instance, pied cuckoos herald the arrival of the Indian monsoon, a swallow for the French and a robin for Americans, are a sign of spring!

For birdwatchers in India (like me!), November to February marks the migration season when winged troubadours voyage from northern lands and flock to our tropical terrains. As they traverse diverse geographies, they navigate across the snow-capped Himalayas, follow the outlines of coastlines, rely on innate cues like instincts and genes, navigate by some visual cues, and eventually gather at their desired wintering grounds.

This blog will chart the repeated refrain of bird migrations to understand the evolutionary history and geography of (feathered) navigation.

Winging it: why do birds migrate?

Demoiselle cranes usually inhabit the northern realms from the Black Sea to northeast China, and travel into Africa and Asia, during winter. The elegant silhouette of birds have found a place in literature and poetry, and there is even a mention of them in our epic poems, the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Image Credits: Bishnu Sarangi via Pixabay.

Through the aeons, our tilted planet has witnessed seasonal changes — in winter, temperatures drop and food sources dwindle, whereas summers are warm, with abundant food — and the evolutionary response of birds was to migrate to favourable climes.

In the Northern Hemisphere, birds embark on a northward migration during spring, capitalizing on the surge in insect populations, blooming plants, and ample nesting opportunities. As winter approaches, the availability of insects declines, and these birds migrate southwards.

However, not all birds migrate. If they can find food all year round in a single location, they tend to stay put. Those that do migrate may not all undertake long, arduous journeys; short-distance migrants descend from high elevation to low, and medium-distance migrants may cover a few hundred kilometres at most.

From a geographical standpoint, long-distance migrants hold clues to the evolution of navigation, and the environmental conditions that trigger their cross-country or cross-continental journeys. We'll be retracing the complex origin of long-distance migrations to reconstruct the climates and contours of the past.

Zugunruhe: why does the caged bird flit?

Over the years, people who'd caged migratory birds noticed and recorded a period of agitation — when birds flitted to a particular side of the cage — during spring and fall. German behavioral scientists termed it zugunruhe meaning migratory restlessness. Zugunruhe is the innate cue that triggers seasonal migrations in birds. Interestingly, the side of the cage that birds flit to isn't randomly chosen either. Studies have shown birds flit to the cardinal direction in which they will migrate.

The evolution of bird migration

One leading theory for avian migration posits that it evolved gradually through the extension of smaller annual movements as birds sought better food sources or breeding grounds. If these movements increased their chances of survival and reproduction, birds passed on migratory behaviour to successive generations. Over time, short journeys to and from a seasonal feeding ground may have expanded due to changes in climate and resource availability.

Environmental cycles, particularly the earth's numerous cycles of change, played a pivotal role in this evolution. Over the past 2.5 million years, the Earth has witnessed more than 20 glacial cycles, the most recent one being the melting and retreat of vast ice sheets, which occurred between 1, 15,000- 11,700 years ago (the last Ice Age — not to be confused with when the dodos went extinct😉). During Pleistocene glaciation cycles, migrants likely retreated to southern breeding grounds, resulting in shorter migrations. As the ice receded, they moved north, seizing renewed breeding opportunities in the emerging, unoccupied habitat.

Interestingly, the present-day migratory patterns of certain birds hold clues not just to past migratory routes, but also to the diversification of species. The article below delves into fascinating details on what we've learned about evolution and speciation through bird migrations.

Flyways: invisible flight paths

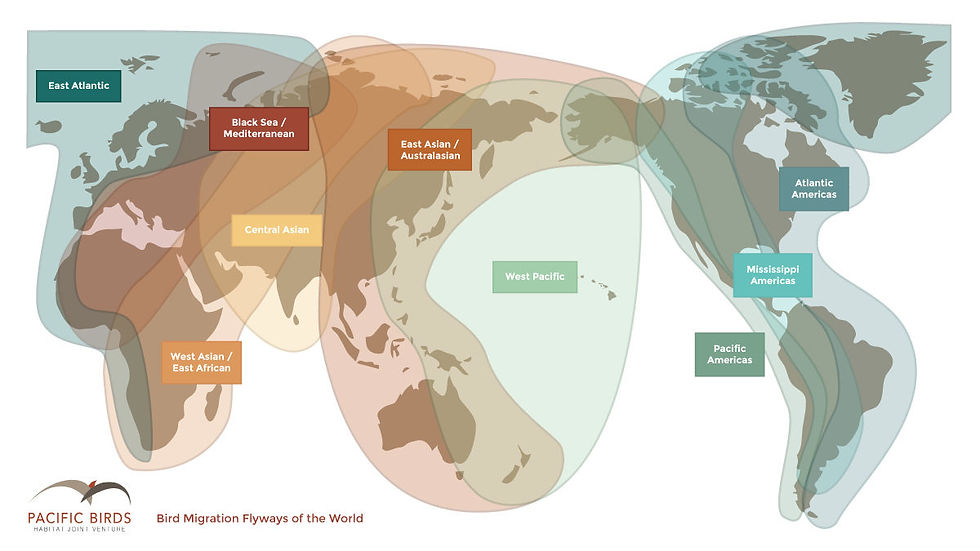

Flyways can be envisioned as migratory roadmaps, guiding the journeys of numerous bird populations across extensive geographies.

There are 3 major flyways along which birds migrate into India:

The Central Asian Flyway (CAF) originates in Siberia, and stretches across the northern and central regions of India, covering parts of West Asia, the Maldives, and the British Indian Ocean Territory. This is the primary route for over 250 species of migratory waterbirds, many of which are under threat.

The East-Asian Australasian Flyway (EAAF), begins in Arctic Russia, encompasses parts of eastern India and the Andaman and Nicobar islands, continues into southeast Asia, and extends to Australia and New Zealand.

The Asian East African Flyway (AEF) is not a north-to-south flyway that spans two tropical countries; connecting the mid-Himalaya ecosystems with sites in eastern and southern Africa.

These flyways, form part of an intricate network, along which birds traverse different ecosystems, countries, and continents. Protecting these avian highways presents an opportunity for nations to safeguard the planet's biodiversity.

With years of citizen science data contributions to eBird, we can retrace the journeys of over 50 frequent flyers that visit India: Migration Maps: India

By clock, or compass, or cue: how do birds navigate?

After years of research into bird migration, we have some understanding of how birds migrate, but new insights continue to flow in.

A favoured theory, the clock-and-compass model suggests that first-time migrants inherit navigational vectors, allowing them to follow seasonally appropriate compass directions to reach their destination or stopover sites. However, much of the research has been biased towards individuals returning to familiar locations, overlooking those who venture into novel regions or habitats.

Birds, it seems, continually integrate cues from previous experiences to create mental maps or even stop signs for navigation. These cues are diverse, ranging from olfactory and celestial to geomagnetic signals. Here's an in-depth article on recent research on magnetoreception in birds, published in the Scientific American: How Migrating Birds Use Quantum Effects to Navigate

Feathers in Flux: Migratory Birds at Risk

Bar-headed geese undertake one of the most iconic high-altitude migrations over the Himalayas, in their annual pilgrimage from Mongolia and the Tibetan plateau to Central Asia. They've evolved to withstand the oxygen demands of their trans-Himalayan journeys, despite the rarefied atmosphere. Image Credits: Lancier via Pixabay.

As yearly travellers, migratory birds are not just at more risk from global crisis, but often, they also exacerbate the issues:

Plastic Pollution: As feathered migrants make their way across continents and waterways, they unwittingly transport plastic between different ecosystems, and across the food chain. Migratory birds are most at risk from plastic pollution, as they travel wide. When they ingest plastic, they may introduce it into remote geographies when they poop, or use it for nesting sites, thereby putting their young at risk too.

Avian Flu Epidemics: in recent years, India has been susceptible to bird flu outbreaks, transmitted via the million avian migrants that visit our tropical country. Like with plastic pollution, migratory birds are at greater risk of avian flu, which can then spread to poultry or resident birds. Just this week, the first-ever deaths in Antarctica penguins have been attributed to bird flu, perhaps transmitted by migratory birds. Mass deaths in migratory populations, like the bar-headed geese, have also been recorded.

Climate Change: Habitat loss is one of the major consequences of climate change; migratory birds are at risk in a world where temperatures are unpredictable, with floods and desertification imminent. As birds travel in search of seasonal resources, climate change has also affected food supplies with delays in insect or aquatic blooms. While some birds are adjusting their migration schedules, or extending their ranges, some changes have been too extreme. Disruptions in bird migrations provide observable and measurable evidence of climate change.

In a sense, migrations reinforce a sense of 'topophilia' — an affinity with one's environment. Though migrations represent a struggle for survival, as individuals leave familiar places to seek better resources in new geographies, there is a strong sense of place.

Through time, humans have migrated for myriad reasons, and continue to do so. Our 'topophilia' is part-nostalgia, part-discovery — at the chance to explore a new geography, which anchors our emotional, cognitive, and cultural identities.

I cannot assume birds feel the same way about migrations, but by tuning in to their repeated refrains over centuries, humans have found solace, meaning and a way to rekindle our bond with Nature.

Book Recommendations

The Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) graciously helped me with this section. The top row features books that explain bird migration, the bottom row, focuses on birds and birdwatching in India. Happy Reading!